By Chaiyatat Ben Bunjapamai, BBLAM

As part of the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investment environment, impact investing continues to receive increased interest as an investment vehicle that can deliver real-world impact. One approach to impact investing is alignment with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are “a set of goals to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure prosperity for all as part of a new, sustainable development agenda.” Funds that claim SDG-alignment tend to be understood as making positive contributions toward the environment and/or society. Therefore, the growing interest in impact investment could require increased scrutinization by regulators and supervisors in assessing how and whether an asset manager’s investments in financial instruments can achieve impact, and whether such claims hold true to the investment policies and strategies that are marketed.

The UN SDGs are part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, providing “call for action by all countries – developed and developing – in a global partnership” to tackle global challenges and end poverty, protect the planet and build more peaceful, prosperous societies by 2030. The SDGs comprise 17 goals, with 160 targets, and 248 indicators, with goals encompassing areas such as climate action, sustainable cities and communities, and poverty. According to a European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) paper, “the framework’s structure is, in its origin, mainly adapted to sovereigns (i.e., most targets are evaluated based on country-level metrics such as the percent reduction in poverty rate). However, growing public pressure and the need for a holistic approach to address global challenges have sparked the need for private sector actors to adjust businesses’ operations in line with the SDG objectives.” In our opinion, because regulators and market supervisors have pushed SDG-alignment onto investment funds and the private sector in order to show “impact,” the risk of greenwashing and/or impact-washing, becomes heightened.

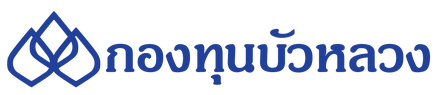

In this UN SDG heatmap based on GICS sector exposure, BBLAM’s sustainability research team adapted a Morgan Stanley framework, showing direct revenue exposure to the SDGs based on the 160 targets and 248 indicators lists as criteria for revenue exposure. SDGs 10, 14,15, and 16 stand out as goals that do not align with any of the 11 GICS sectors listed, because of the SDG framework mainly aligned to sovereigns, and do not have indicators that can be used by the private sector. In a quick review of five SET ESG AAA-rated companies (all SET-50 listed), all five companies list one or more of SDG goals 10, 14, 15, and 16; and list SDG goals that we identify as not having direct revenue exposure to that companies’ sector, according to the heatmap above. None of the five companies mention the SDG targets or indicators, just the goals. Nevertheless, from a stakeholder perspective such claims could be understandable based on business operations, but perhaps the SDGs are more suited to identify which companies could potentially benefit in the long run from alignment to sovereign initiatives, based on the SDGs, rather than aligning with the SDGs themselves.

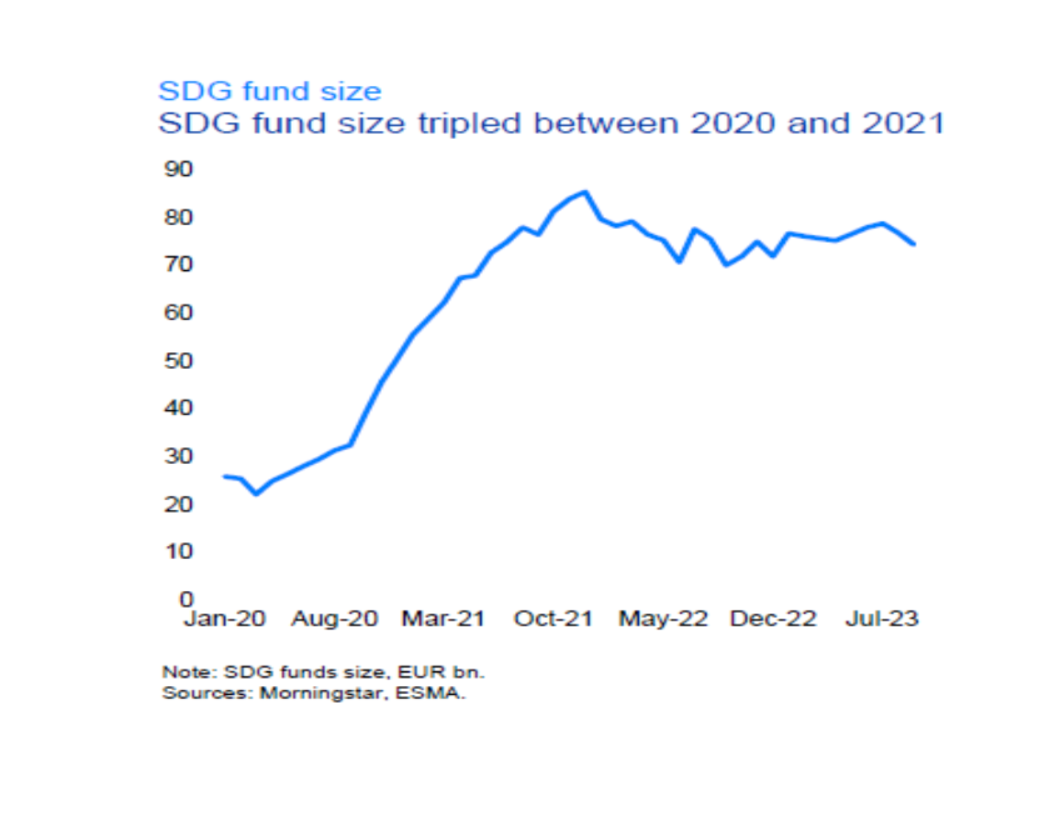

The growth of ESG-related financial products stems from public interest in seeing financial contributions to achieving a more sustainable economy and to achieving the SDGs, and as a result has led to the popularity of SDG-aligned funds’ AUM reaching EUR74 billion in September 2023. These funds are crucial to bridging a financing gap estimated at roughly US$ 4 trillion, but they also lead to impact washing concerns. For example, SDG indicator 5.6.2 states the “number of countries with laws and regulations that guarantee women aged 15-49 years access to sexual and reproductive health care, information and education,” while SDG indicator 14.6.1 states “progress by countries in the degree of implementation of international instruments aiming to combat illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing,” which are clearly aimed at sovereign, rather than private sector action. Furthermore, the ESMA identifies impact-washing, including by misusing SDG targets, as a key issue in its progress report on greenwashing.

While this does not necessarily mean that these companies are not creating environmental and/or social impacts from their business operations, it certainly highlights the importance of clarifying how and whether to align the UN SDGs framework to the private sector, not just sovereigns. In the context of Thai equities, our example above illustrates the need for more clarity in aligning company and fund level disclosures to clearly defined metrics, rather than simply increasing the mere amount of disclosure and ignoring the quality of disclosure. To prevent the effects of greenwashing, and more specifically impact or SDG-washing, the asset management industry along with the regulators, market supervisors, and corporates must evaluate how to best balance impact with financial materiality, ultimately preventing impact engagement at a superficial level, as shown to be done with the UN SDGs.